Ecosystems and Biodiversity Lesson 9 : Most Wanted - Invaders of the Great Lakes Region

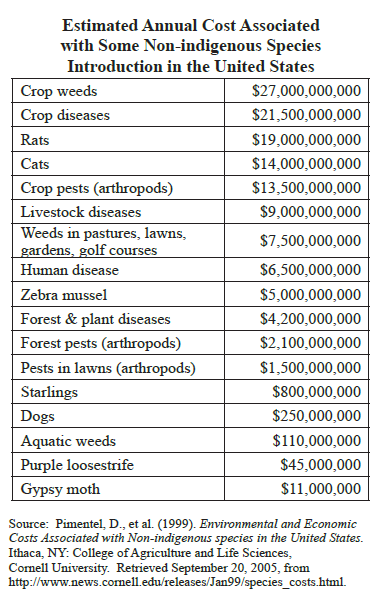

An invasive species is an alien species whose introduction causes, or is likely to cause, economic or environmental harm or harm to human health. Today, out of approximately 750,000 species in the United States, at least 50,000 of them are nonnative. Of these, only a minority have caused harm to agriculture, industry, human health, and/ or the natural environment, costing the United States more than an estimated $138 billion each year. Worldwide, invasive species are considered a leading cause of extinction, second only to habitat loss. In the United States, invasive species are the main factor in the decline of 42% of species protected by the Federal Endangered Species Act. In the Great Lakes region, invasive species now represent the greatest threat to biodiversity.

Estimated Annual Cost Associated with Some Non-indigenous Species Introduction in the US

Anywhere you look throughout the Great Lakes region, every type of natural landscape is threatened by invasive species. In this century alone, forests have been subjected to the devastating effects of chestnut blight, Dutch Elm disease, gypsy moth, and, more recently, the emerald ash borer and beech bark disease. To grow food, American farmers annually suffer tens of billions of dollars in crop damage and losses caused by a multitude of nonnative plant, animal, and pathogen species. People routinely struggle to keep their homes and lawns free of pests such as rats, cockroaches, dandelions, and other weeds. Purple loosestrife crowds out wetland plants while spotted knapweed invades many once-pristine coastal dunes. Since the 1800s, more than 140 non-native organisms have become established in the waters of the Great Lakes (also impacting inland lakes, rivers, and streams).

Because organisms compete for resources such as nutrients, space, water, and sunlight, when nonnative species are introduced into an ecosystem, they often do not have natural predators or diseases; thus, there may be nothing to control their spread. The primary threat from non-native species is that yhey may use up enough of the natural resources to outcompete the natives, leading to a decrease in biodiversity. In animals, this competition sometimes is easier to observe. For example, European starlings compete directly with native hole-nesting bird species for cavities in trees and other suitable nest holes. Lampreys directly attack and parasitize native fishes in the Great Lakes. Among plants, the competition for resources is less visible to humans because plants are competing for sunlight, water, space, and nutrients in the soil. Other ways that invaders may upset the balance of native ecosystems include: altering hydrological conditions, soil characteristics, natural succession, fire intensity and frequency, poisoning or repelling native insects, serving as reservoirs for plant pathogens, and increasing predation on nesting birds.

Methods of Introduction

Most invasive species arrive in association with human activities or transport. As the world’s human population has grown increasingly mobile with more and more global trade, the number of biological invasions has also increased. Global trade is extremely dependent on the shipping industry, as almost all U.S. cargo (over 99% by weight and 61% by value) is transported by ocean-going ships. The quantity of goods shipped to and from ports within the Great Lakes increased dramatically with the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. The Seaway allowed deep draft ocean-going ships to move directly between the Great Lakes and international ports for the first time. Since its opening, more than 2 billion tons of cargo, valued at an estimated $300 billion, have been transported through the Seaway. Today, approximately 25% of all traffic moving through the Seaway moves to and from international ports, especially those in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

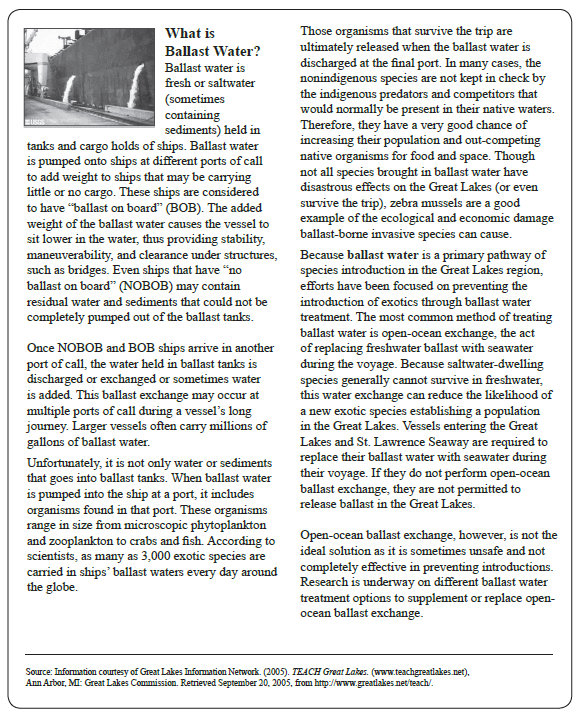

While the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway and other canals (Erie Canal in 1825, Welland Canal in 1829, Sault Sainte Marie Canal in 1855) have allowed some cities in the Great Lakes to become economically important international ports, they have also contributed to significant increases in the introduction of non-native species into the region. Numerous forest and agricultural pests first arrived in North America as contaminants of goods transported on ships. For example, agricultural produce, nursery stock, cut flowers, and timber can harbor rats, mice, insects, plant pathogens, slugs, and snails. Weeds may be carried as contaminants of seed shipments. Pathogens sometimes arrive as unintended contaminants of plant materials. Fish and shellfish pathogens and parasites have been introduced unintentionally on infected stock destined for aquaculture. Crates and containers used to transport goods can harbor snails, slugs, mollusks, beetles, and other organisms. Finally, ballast water that is released from ships when cargo is loaded or unloaded is considered the primary pathway for invasions of aquatic organisms into the Great Lakes.

More than 87 non-native aquatic species, including the zebra mussel, Eurasian ruffe, and round goby, have been accidentally introduced into the Great Lakes in the 20th century alone.

Aside from ship-related introductions, invasive species are introduced by the following three methods:

1. Accidental (or unintentional) release such as release of aquarium pets and plants, escaped cultivated plants or animals from gardens or ponds, and release of unused live bait. For example, the Asian carp was being raised on fish farms in Arkansas when it escaped into the wild during floods. Rusty crayfish were probably introduced by fishermen who released unused live bait into the wild. Plants used for agriculture, landscaping, and aquariums have escaped into the wild.

2. Deliberate (or intentional) releases of fish or animals (especially game) used for stocking. For example, the ring-necked pheasant, common carp, brown trout, Coho salmon, and Chinook salmon were all intentionally stocked for fishing and hunting purposes. The house sparrow was released with the hopes of controlling agricultural pests. The European starling was introduced by one man inspired by Shakespeare.

3. Movement through or along canals, railways, or highways. For example, the alewife, sea lamprey, and white perch all likely swam into the Great Lakes through newly constructed canals.

Prevention and Control

The first and most effective means of protection is through the prevention of intentional or unintentional entry of harmful invasive species. On February 3, 1999, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13112, requiring coordination and enhancement of Federal activities to control and minimize the economic, ecological, and human health impacts caused by invasive species. The same order also established the National Invasive Species Council to oversee a management plan detailing the goals and objectives of the federal agencies and departments involved, which include the following: U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), USDA’s Forest Service, U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, U.S. National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In Michigan, agencies involved in protecting our resources from invasives include the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Department of Agriculture (MDA), Michigan Sea Grant, and Michigan State University Extension.

Although invasive species may be extremely difficult to get rid of once established, it is still extremely important to control their numbers and distribution. Tactics may include detecting, eradicating, managing, or controlling specific pests that are already established. For example, millions of dollars are spent every year on control programs related to species such as Eurasian milfoil, sea lamprey, emerald ash borer, gypsy moth, and purple loosestrife. Some examples of methods used to control existing populations include:

• Chemical control: For example, the lampricide TMF is used to control sea lamprey populations, herbicides may be used to control agricultural weeds and aquatic plants, and pesticides may be used to control agricultural and forest pests.

• Barrier construction: Barrier methods, including sound waves, electrical impulses, and visual and physical deterrents, can help prevent the spread of exotics in smaller waterways like canals and streams.

• Physical removal: Harvesting small populations of aquatic plants, for instance, can act as a temporary control in smaller inland lakes and waterways.

• Biological control: Very carefully selected non-native species, usually predators, can be introduced to control population growth of another invasive species. A good example of this is work done with insects that specialize in eating purple loosestrife.

• Public education: Educating people about how invasive species can be spread and ideas for prevention may be the most effective preventative method used to control the spread of invasives.

What Can Individuals Do to Help Prevent the Spread of Invasive Species?

• Educate yourself and others about the problem of invasive species.

• Learn to identify native and non-native plants and animals in your area.

• Find out who to contact to report new invasions or to receive guidance on controlling invasives on your property.

• Landscape with native plants or non-invasive ornamental plants appropriate for your area.

• Do not bring plants, fruits, soil, or animals into the country from overseas, without first having them inspected by the proper officials.

• Adopt a local natural area and work with the appropriate officials on an eradication plan for removing invasive plants.

• Clean boats and boating equipment before transporting them from one body of water to another to avoid spreading aquatic pests.

• Never use exotic species as bait and never release aquarium plants or animals into the wild.

Source: Adapted from U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2001). Wild Things 2001: Investigating Invasive Species (p. 21). Shepherdstown, WV:

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved October 3, 2005, from http://www.wildthingsfws.org/WT2001/guide_instructions.htm.

What is Ballast Water?